What Makes A Martial Art?

A Definitive Definition.

Oh boy, do we love to argue over what counts as a martial art, and whether “it’s the art, or the artist”. Let’s dig in.

First, we need to define what Martial Arts even is.

This is problematic, to say the least. Asian terms like Budo, bujutsu, and wushu all generically mean “martial arts”. What are they applied to? The large variety of combat systems present in the culture. To confound things, folks in China do, indeed, use the term “kung fu” as a short hand for martial arts, though the term is about as generic as it gets, meaning the result of hard work over a long-/life-time. It, of course, can be, and is used more broadly, but the term has gained and maintained popularity for martial arts.

As a side note, and I shouldn’t have to say this, kung fu does not refer to any one style, and so lumping all kung fu together to make a judgement is fallacious from the ground up. Just stop doing that. Stop it.

What about in the west? Where did we decide to start using the term? Well, it gained popularity in the 1970s (I believe) as a translation or interpretation of budo. However, There is a passage from one of Chaucer’s works (I can’t find the reference) where he references “The arts martial” (spelling normalized), and he refers to the typical activities of a medieval soldier.

Now, clearly, we did not adopt the term martial arts from Chaucer. The point of bringing him up is in the use of the term “art”.

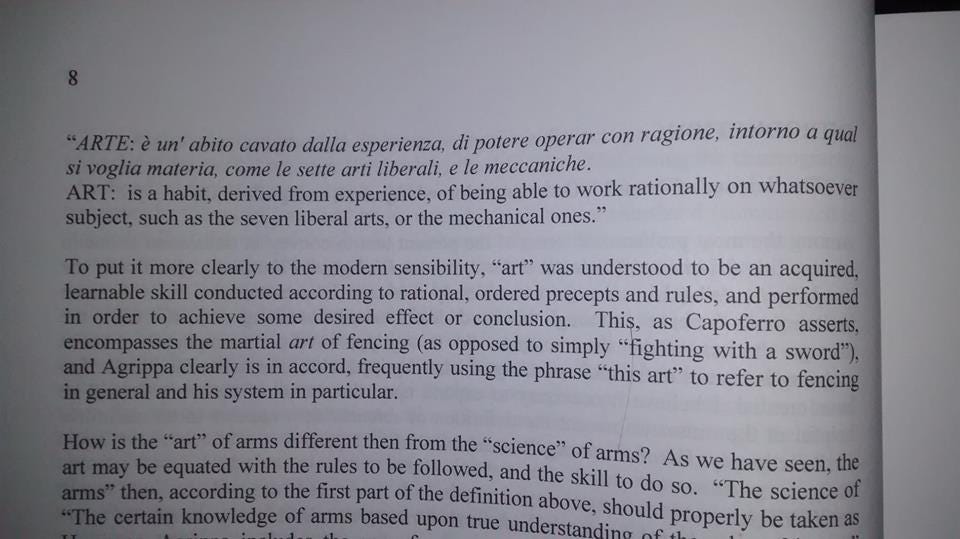

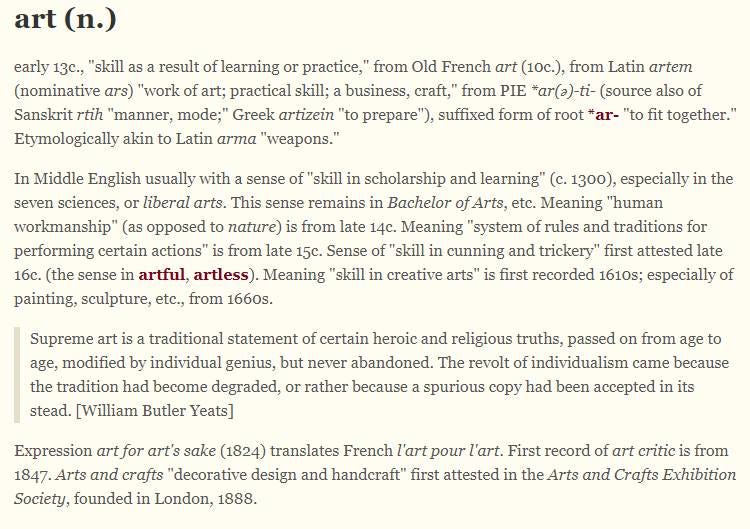

I cannot count how many times I’ve seen someone argue that art means “expression”. It simply does not. Art means “a learned skill”.

And the word has been used across latin-language cultures for a long time. In fact, there are old Italian dictionaries to evidence the fact.

So what about the term “Martial”. Pretty straightforward, it means “warlike, or pertaining to war” or more generally “things pertaining to the Roman god, Mars.”

But back to the Asian terms, what about bu/wu 武 ? This also means “warlike” or “military”. Likewise, jutsu/shu 術 means “art or skill”. Rarely do Asian translations ever match up so exactly, but in this case, they do.

So we’ve solved it, martial arts are the skills of war and warriors. Done, easy.

…not so fast.

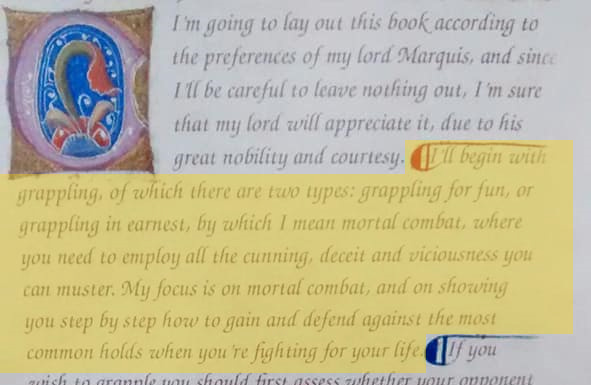

These terms, English, Latin, Chinese, Japanese, are just big umbrella terms that haven’t seen much popularity in common speech until the 20th century. Most of the time, whatever art you trained was referred to by its own name, and not by some generic umbrella term. On top of this, folks styles were often looked at as separate and different from military (or, at least, “serious”) styles. As a case in point, there is a journal entry from a Chinese general making fun of village styles for being flowery. We see in Fiore Dei Liberi’s fighting treatise that he classifies two forms of wrestling, for play, and “in earnest”.

Of course, you can even look back to Greece and Rome with their competitive games and gladiatorial combat being nothing like their military tactics. And in many HEMA sources, we see that instructions for duelling are vastly different from instructions for self defense or military battle.

Does this mean that combat sports are not martial arts? Well, I suppose that depends on who you ask. But Pietro Monte believed wrestling was fundamental as the base to armed combat. Fiore’s grappling, while being “in earnest” and not for fun, was the foundation of his armed combat. In fact, the world over, we see grappling arts as either the foundation for armed combat, or the empty hand counterpart to it. The Japanese have no native boxing arts, but every armed combat art also has some form of jujutsu (oversimplified term…) to accompany it. Most every Chinese art has some form of qinna embedded in it, and while they seem to overwhelmingly support boxing styles, most of them also have one or more weapons trained in support. And then when we look at Shuai Jiao, or Jiao Di as it was once known, it was used as training in the military.

The lines between mortal combat and sport blur heavily. And what about modern warfare? Where does mechanized combat come in? Is gun fighting a martial art? I would argue yes. Is launching missiles from mobile platforms a martial art? I suppose by strict definition, it is. What about drone strikes? Is that martial arts? If not, why not? This is the problem we have with such definitions. If we want to be literal to the terminology, we cut of related things that might be considered “sport” and we include things like programming a computer for an unmanned attack on an enemy base. If we are not so literal, where do we put the lines? Let’s say we don’t include anything that doesn’t involve humans vs other humans on some sort of actual, physical battlefield or other stage. While arbitrary, I could roughly accept that idea for the sake of an argument. But what about the other end of the spectrum, in sport and entertainment? Let’s go ahead and include all combat sports where two or more people are trying to directly, physically assert dominance over the opposition. This means even highly specialized arts like Sumo and shin kicking are martial arts. I think I might be ok with that. But what about the arts that focus on performance for spectacle? Like modern competition wushu where they just perform forms and choreography? They’re using many of the same moves the fighters do, even if overly stylized. Is it enough to have the appearance of combat skills? I would argue no. But maybe you would argue in its favor. Why?

At the end of the day, the things that are squarely in the middle of that spectrum are fairly easily defined as martial arts by one or more set of criteria. It’s the edges where it gets fuzzy. So perhaps when you feel the need to argue about what is and isn’t a martial art, you also label your criteria for what you mean, because there isn’t a universal definition, and there are many related skills that may or may not fit, depending on your definition.

For the sake of our argument, let us now define martial arts as a broad umbrella term for the trained skills of physical conflict resolution between two or more humans. There’s still a lot of grey area there, but it’s a usable definition.

What’s Apparent vs What’s Real

When it comes to determining what “makes a martial art” we have to understand that training has many many modalities, and what something looks like, may not be what it is. Sometimes this seems to be done on purpose as some sort of protection against the opposition learning your tricks, but more often, it ends up being some sort of mnemonic device or remedial step to help illustrate a specific aspect of the “problem solving”.

There is, of course, danger here. Many who are under-qualified to be teachers will take these useful but ultimately inaccurate and faulty methods to be the full expression of the art. They fail to bring the student in from the exaggeration, leaving only the clever students to discover the adjustment “back to center” and the less clever students to be frustrated. Many training methods are even free of context, leaving the applications open to interpretation. If the time is not taken in training to explore the possibilities of the abstractions, they remain intangible and largely under used.

But beyond the exaggerations and abstractions, sometimes folks just plain old stylize things to differentiate themselves from the competition. This doesn’t always work out as a beneficial thing, and Rory Miller even warns against such mushroom stamping in his book Conflict Communication. But vanity issues aside, there’s another problem with excessive stylization.

When your training seeks to appear a certain way, for whatever reason, you’re not just putting on a show, you’re making a statement that, “this is what my method does!” and then when it comes to the test, and stress dumps the stylization out the window in favor of normal human movement, people who see this will be confused, and may ultimately decide you can’t practice what you preach because the training doesn’t look like the test.

Now, there is something to be said in favor of this. We are very aware of the SAID principle in the modern world, and it’s just a fact that the training needs to mirror the test as closely as is sustainable. You can’t become a better carpenter by building PCBs. You do it by cutting and joining wood over and over again until it feels like second nature, and the results are consistent and reliable.

On the other side of the argument, there are many “tests” that are just not sustainably reproducible in training because they carry too much risk of injury, or produce too much stress and fatigue to recover from in a timely fashion to continue training on an appropriate schedule. This leads to separating many aspects that work in concert into distinct training protocols to preserve the health of the trainee, and allow development with less interference effect from less compatible aspects. At some point, training necessarily starts resembling the martial arts equivalent of Crossfit, or the Conjugate method.

Now think back a few sentences to what I said about certain methods being relatively free of context. This means there is going to be a necessary amount of stylization for the sake having a training standard, even though the applications may be vastly different. This leads to concepts like the three levels of bunkai in karate.

The simple fact is that what is apparent is not always what’s real, and striving to look a certain way is just not a valid measure for good the training is, nor is analyzing someone’s training on the appearance alone a valid way to critique the method. So we can say, for pretty certain, that appearance is NOT what makes a martial art.

It’s Not The Martial Art, It’s The Practitioner

This old standby is aggravating because it is simultaneously true and false (It’s not a paradox, it’s true and false for different reasons.)

If we take what we said above, about training methods and appearance, then we can continue on to say that the training method matters a lot regardless of appearance. Between the SAID principle and the necessary division of stresses for sustainability, we can say that there are going to be training methods that get you to a goal quicker, and those that hold you back. Of course, not everybody responds the same to all training, so there is a range of what will or may work to that end. Some folks will be non-responders to your “perfect” system, and others will be hyper-responders to things that shouldn’t work by any objective measure.

So here we have the support of the argument that it’s in the hands of the practitioner (or the interplay of the practitioner, his peers, and teacher(s)). It is a very strong argument. After all, if it works, it’s not wrong!

^Rumble video link: If It Works, It's Not Wrong!

However, the elephant in the room is that an inappropriate tool is of no use to a task it’s not suited for. A saw is not a plane is not a wrench, etc. Of course, you can kind of use certain tools in functions they’re not designed for, but they make you work twice as hard as you need to, do less precise work, and are generally miserable to use as such.

This brings up how some folks sub-classify categories of martial arts. One of the big ones is the division of Traditional Martial Arts (TMA) and Combat Sports. Some will also make a distinction between Traditional and Classical (I am a fan of this argument). and some will place Reality-Based Self Defense (RBSD) and/or Combatives in a separate category. Of course, this categorical thinking presents grey area problems of its own, similar to the definition of martial arts. But this division is attempting to provide context for the given art.

Context is king.

It is entirely possible for something to work in one place and fail in another. Each and every context has different limitations, and resolution goals, and thus requires a different toolbox, or at least a few different tools. This is where TMA gets into trouble. The entire concept of tradition is flawed. It literally just means something passed down. And things that are passed down are typically done so because “if it ain’t broke, don’t fix it”. Cynicism aside, tradition once served a very important purpose. Historically, people were typically illiterate, and science was bad, or non-existent. This means that the older, more experienced generation needed to teach the younger generation how to do things so they didn’t have to make so many mistakes on their own. It was a necessary thing. But enter hierarchical culture, and it quickly becomes an “if it ain’t broke…” excuse. You have people brainwashed that their elders knew everything there was to know, or that it would be disrespectful to try to improve upon something.

In the martial arts, this creates a romantic notion of some golden age where the elders were mythical heroes who had it all figured out, and we must preserve their magical elixir. Except, history kept marching on. Pressures kept changing. Context changed. In many cases, the pressures and stresses got lighter, so the arts didn’t have to evolve to grow stronger. As nations civilized, street fighting went down. As honor cultures gave way to dignity cultures, the need for physical self defense decreased. This means that more and more folks could train without ever being tested, and opened the door for stagnation, and maladaptation.

In some ways, this does mean that our elders were doing better, because they had to live the conflict, while we get to imagine it. As a member of the HEMA community, I can say that one of the big struggles is understanding the context. We simply can’t train safely with sharp swords and spears, and we will likely never find ourselves in a duel to the death. We have no modern measure of how that would work. In these cases it becomes so valuable to look to the accounts in the history, because the men who came before us were actually living and fighting in the context we read about. They had insight we will almost certainly never have because it is a context that simply doesn’t exist anymore. But this also means that the transfer of those skills to the modern day is not very strong, because of that void in context.

This is where I support the division of TMA and classical styles. Classical means “belonging to the highest class, or approved as a model”. It is something that is serving the same or similar function to something established as high quality, and conventionally refers to something newer or living being similar to something older or dead.

In the martial arts, this will generally apply to arts that have a historical basis, but continue to try to adapt to the changes in context as they happen. So an art that was designed for self defense against bandits may maintain its historical framework, but continues to evolve based on the self defense needs of today. In my opinion, this is a much more robust practice since we don’t just look at tradition, but try to understand what problems they were trying to solve, and then compare and contrast that to the current problems, and add, remove, or change things as necessary. This allows an art to continue to serve its purpose, even as context changes. The key to this difference is understanding the context in history, and how that context has changed.

The RBSD and combatives crowds are attempting this, with varying success, with worrying about the history, and only focusing on right now. And then we have the combat sports.

What a contentious subject this is. Lovers of combat sports treat them like they’re Excalibur, and haters treat them like they’re uncivilized thugs. The truth is that combat sports exist for two reasons. One, people love to play dominance games, especially young men. We have cave paintings of wrestling, for fuck’s sake. The other reason they exist is because some folks are not satisfied with leaving their hard earned skills untested, and instead of risking their lives in illegal fights, or joining armed and otherwise security services, they decided to compete in something that is satisfying enough while being safer than facing down a 1950s whistling knife gang. It serves as a test of sorts for them to verify their skills, and give them direction for continued training.

The down side of this is that they’ve immediately changed the context of their art from the beginning. Assaults are nothing like honor duels are nothing like battlefield combat is nothing like prizefighting. And while many combat athletes do well in armed services and civilian altercations it is not a spotless record. Because context matters. Even between the different combat sports, when people switch to another one, especially without a period of specific training, they tend to do poorly.

What this all boils down to is that fact that it’s not just the fighter. It is the toolbox as well. You just can’t bring a carpenter’s toolbox to an auto garage and expect to be able to rebuild an engine.

So What Makes A Martial Art?

A martial art, being loosely defined as a trained skillset oriented around resolving physical conflict between two or more humans, is made of two distinct parts: The Training Method, and The Toolbox.

The toolbox must be appropriate to the task at hand, and the training method must sufficiently prepare you to use the tools in that toolbox for said task.

If you judge an art only by its toolbox, or its method, you are missing a part of the picture, and as we discussed, what is apparent is not always what is real.